Metformin might help you live a longer, healthier life - But in most countries you will have to convince a doctor to prescribe it

Imagine a country in which it is possible to walk into a pharmacy and, without a prescription, buy a 15 cent pill that, if taken once or twice a day, could help prevent diabetes, cancer, heart disease, and dementia.

OK, now stop imagining. Because you don’t need to. That country already exists.

Even as the evidence mounts that metformin might delay most major diseases of aging in humans, it remains stuck behind the counter—available only by prescription—thanks to its designation as a regulated substance in most countries, including the United States and Australia.

But in countries like Thailand, metformin can be picked up at every corner pharmacy.

Now, before going any further, let me remind you: I’m just a scientist with a Ph.D., and not a “real doctor.” I don ‘t give medical advice. I’m not going to tell you, or anyone else, that you should take metformin. What I am going to do is shed light on the current discussion around metformin, while highlighting the research I’ve seen in my own lab and the research coming out of the labs of my colleagues. If this helps you make your own health decisions, through conversations with your doctors, I’m pleased.

The first question most people ask when investigating any medication is “are there side effects?” And the answer, no matter the medication, is always “yes, there are always potential side effects.”

Indeed, in the case of metformin, there can be rare and serious side-effects — including a condition called lactic acidosis, which can come with serious damage to people’s livers and kidneys. The most common side effect, though, is stomach discomfort.

But it’s not metformin’s side effects that keep doctors from prescribing this drug to their patients. Rather, it’s the “on-label” purpose of the medication—diabetes. Just about every day, it seems, I hear from someone who tells me their doctor won’t prescribe them metformin even though their blood sugar and hemoglobin A1C tests indicate that they are almost diabetic. Only after they have full-blown diabetes then will the doctor prescribe a medicine that could prevent it.

This is craziness. Health problems don’t begin at a certain number. Diseases exist on a continuum.

That’s why I believe that safe, cheap interventions—whether they be drugs or supplements or lifestyle changes—can and should be used to prevent diseases, not just to treat them.

Owing to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938, which rightly put up strict regulations, there is a stigma about anything with the name “drug.” But most drugs are simple molecules, just like the natural ones. This doesn’t mean they are risk free—not at all. Some drugs are highly toxic. But so are many natural molecules, too.

Metformin is a derivative of a natural molecule called a “biguanide,” from a flower called Galega officinalis, also known as “goat’s rue” or “French lilac.” It has been used as an herbal medicine in Europe for centuries. In 1957, Frenchman Jean Sterne published a paper demonstrating the effectiveness of oral dimethyl biguanide to treat type 2 diabetes. Since then, the drug has become one of the most widely taken and effective medicines on the globe. It’s among the medications on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines, a catalog of the most effective, safe, and cost-effective therapies for the most prevalent medical conditions. As a generic medication, it costs patients less than $5 a month in most of the world.

More than 60 years of research into metformin and its use by hundreds of millions of people across the globe has given us very solid footing: This drug is quite safe. It should not be in the same category as cancer chemotherapies, blood thinners, and opioids.

That’s an opinion based only on what we already know metformin is capable of doing for people who take it. But what if it does even more?

Back in 2013, shortly after I assisted on a study demonstrating that metformin improves both healthspan and lifespan in mice, a professor from across the river approached me after an event at Harvard.

Like a lot of people who have considered taking metformin, the professor wasn’t diabetic or even pre-diabetic, and so he couldn’t be prescribed the medication on-label, at least not in the United States. But, he noted, “I’m not getting any younger.”

And, as it happens, he was soon headed to a conference in Thailand.

“So I don’t think it’s a question of whether I’ll start taking it,” he said. “It’s just a matter of when. So what do you think?”

I told him then what I told you a few moments ago: I’m a scientist, not a physician. The study we had published was in mice, not humans. That’s always important to remind people, even fellow academics.

In mice, even a very low dose of metformin has been shown to increase lifespan by nearly 6 percent, though some have argued that the effect is due mostly to weight loss. Either way, that could amount to years of extra healthy years for humans, with an emphasis on healthy—the mice showed reduced LDL and cholesterol levels and improved physical performance. As the years have gone by, the evidence has mounted. In twenty-six studies of rodents treated with metformin, twenty-five showed protection from cancer.

Since then, the evidence has grown that metformin may have beneficial effects in humans that go well beyond its long-time role in diabetes control and cancer prevention.

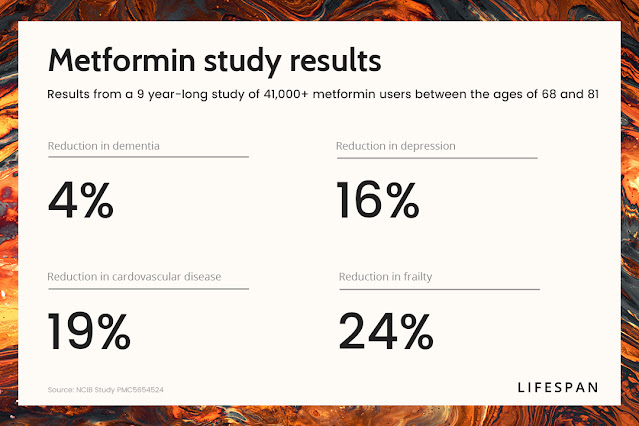

A study of more than 41,000 metformin users between the ages of 68 and 81 concluded that metformin reduced the likelihood of dementia, cardiovascular disease, cancer, frailty, and depression, and not by a small amount. In one group of already frail subjects, metformin use over the course of nine years reduced dementia by 4 percent, depression by 16 percent, cardiovascular disease by 19 percent, frailty by 24 percent, and cancer by 4 percent. In other studies, the protective power of metformin against cancer has been far greater than that. Though not all cancers are suppressed––prostate, bladder, renal, and esophageal cancer seem recalcitrant––more than twenty-five studies have shown a powerful protective effect, sometimes as great as a 40 percent lower risk, most notably for lung, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast cancer.

These aren’t just numbers. These are people whose lives appear to have been improved by using a single, safe drug that costs less than a cup of really bad coffee.

A new study published just a few weeks ago in Annals of Family Medicine adds an intriguing new piece of information to our evolving understanding of this medication.

In an observational cohort study, using data from more than 73,000 male patients over the age of 50 with type 2 diabetes, the researchers found that African American patients who used metformin were less likely to develop dementia.

This study adds two intriguing insights to our growing understanding of metformin.

First, given the differences seen in African American and caucasian patients (the latter of which enjoyed either no advantage or only a very modest one when it came to dementia) we may be beginning to see the ways in which genetics plays a significant role in how different people will benefit from metformin use.

Second, the effect on dementia is yet another clue that the biological programs impacted by metformin may exist significantly upstream of the conditions it impacts. Indeed, metformin might not work on diabetes and dementia, or even both – it might work on aging itself, which is the single biggest risk factor for both of these diseases. If that is the case, it is not unlikely that future studies will continue to demonstrate an effect on other age-aggravated diseases.

This, of course, aligns to hypotheses that have been rather famously proffered by Nir Barzilai, whose Targeting Aging with Metformin (TAME) trials may have a tremendous impact on the prescribing paradigm.

With more and more positive data accumulating, will metformin be used more widely to prevent age-related diseases? Will it be the first drug to be prescribed specifically for the condition of aging?

Barzilai believes that day is coming. He has predicted that if the technologies available now are used widely, and those like cellular reprogramming and senescent cell deletion come to fruition, the traditional Hebrew blessing “Ad me’ah ve-essrim shana,” or “May you live until 120,” may need updating, for it will be a wish not for a long life but for an average one.

Imagine that.

Republished from: https://lifespanbook.com/metformin-pill/

OK, now stop imagining. Because you don’t need to. That country already exists.

Even as the evidence mounts that metformin might delay most major diseases of aging in humans, it remains stuck behind the counter—available only by prescription—thanks to its designation as a regulated substance in most countries, including the United States and Australia.

But in countries like Thailand, metformin can be picked up at every corner pharmacy.

Now, before going any further, let me remind you: I’m just a scientist with a Ph.D., and not a “real doctor.” I don ‘t give medical advice. I’m not going to tell you, or anyone else, that you should take metformin. What I am going to do is shed light on the current discussion around metformin, while highlighting the research I’ve seen in my own lab and the research coming out of the labs of my colleagues. If this helps you make your own health decisions, through conversations with your doctors, I’m pleased.

The first question most people ask when investigating any medication is “are there side effects?” And the answer, no matter the medication, is always “yes, there are always potential side effects.”

Indeed, in the case of metformin, there can be rare and serious side-effects — including a condition called lactic acidosis, which can come with serious damage to people’s livers and kidneys. The most common side effect, though, is stomach discomfort.

But it’s not metformin’s side effects that keep doctors from prescribing this drug to their patients. Rather, it’s the “on-label” purpose of the medication—diabetes. Just about every day, it seems, I hear from someone who tells me their doctor won’t prescribe them metformin even though their blood sugar and hemoglobin A1C tests indicate that they are almost diabetic. Only after they have full-blown diabetes then will the doctor prescribe a medicine that could prevent it.

This is craziness. Health problems don’t begin at a certain number. Diseases exist on a continuum.

That’s why I believe that safe, cheap interventions—whether they be drugs or supplements or lifestyle changes—can and should be used to prevent diseases, not just to treat them.

Owing to the Federal Food, Drug and Cosmetic Act of 1938, which rightly put up strict regulations, there is a stigma about anything with the name “drug.” But most drugs are simple molecules, just like the natural ones. This doesn’t mean they are risk free—not at all. Some drugs are highly toxic. But so are many natural molecules, too.

Metformin is a derivative of a natural molecule called a “biguanide,” from a flower called Galega officinalis, also known as “goat’s rue” or “French lilac.” It has been used as an herbal medicine in Europe for centuries. In 1957, Frenchman Jean Sterne published a paper demonstrating the effectiveness of oral dimethyl biguanide to treat type 2 diabetes. Since then, the drug has become one of the most widely taken and effective medicines on the globe. It’s among the medications on the World Health Organization’s Model List of Essential Medicines, a catalog of the most effective, safe, and cost-effective therapies for the most prevalent medical conditions. As a generic medication, it costs patients less than $5 a month in most of the world.

More than 60 years of research into metformin and its use by hundreds of millions of people across the globe has given us very solid footing: This drug is quite safe. It should not be in the same category as cancer chemotherapies, blood thinners, and opioids.

That’s an opinion based only on what we already know metformin is capable of doing for people who take it. But what if it does even more?

Back in 2013, shortly after I assisted on a study demonstrating that metformin improves both healthspan and lifespan in mice, a professor from across the river approached me after an event at Harvard.

Like a lot of people who have considered taking metformin, the professor wasn’t diabetic or even pre-diabetic, and so he couldn’t be prescribed the medication on-label, at least not in the United States. But, he noted, “I’m not getting any younger.”

And, as it happens, he was soon headed to a conference in Thailand.

“So I don’t think it’s a question of whether I’ll start taking it,” he said. “It’s just a matter of when. So what do you think?”

I told him then what I told you a few moments ago: I’m a scientist, not a physician. The study we had published was in mice, not humans. That’s always important to remind people, even fellow academics.

In mice, even a very low dose of metformin has been shown to increase lifespan by nearly 6 percent, though some have argued that the effect is due mostly to weight loss. Either way, that could amount to years of extra healthy years for humans, with an emphasis on healthy—the mice showed reduced LDL and cholesterol levels and improved physical performance. As the years have gone by, the evidence has mounted. In twenty-six studies of rodents treated with metformin, twenty-five showed protection from cancer.

Since then, the evidence has grown that metformin may have beneficial effects in humans that go well beyond its long-time role in diabetes control and cancer prevention.

A study of more than 41,000 metformin users between the ages of 68 and 81 concluded that metformin reduced the likelihood of dementia, cardiovascular disease, cancer, frailty, and depression, and not by a small amount. In one group of already frail subjects, metformin use over the course of nine years reduced dementia by 4 percent, depression by 16 percent, cardiovascular disease by 19 percent, frailty by 24 percent, and cancer by 4 percent. In other studies, the protective power of metformin against cancer has been far greater than that. Though not all cancers are suppressed––prostate, bladder, renal, and esophageal cancer seem recalcitrant––more than twenty-five studies have shown a powerful protective effect, sometimes as great as a 40 percent lower risk, most notably for lung, colorectal, pancreatic, and breast cancer.

|

| A study of more than 41,000 metformin users between the ages of 68 and 81 concluded that metformin reduced the likelihood of dementia, cardiovascular disease, cancer, frailty, and depression. |

These aren’t just numbers. These are people whose lives appear to have been improved by using a single, safe drug that costs less than a cup of really bad coffee.

A new study published just a few weeks ago in Annals of Family Medicine adds an intriguing new piece of information to our evolving understanding of this medication.

In an observational cohort study, using data from more than 73,000 male patients over the age of 50 with type 2 diabetes, the researchers found that African American patients who used metformin were less likely to develop dementia.

This study adds two intriguing insights to our growing understanding of metformin.

First, given the differences seen in African American and caucasian patients (the latter of which enjoyed either no advantage or only a very modest one when it came to dementia) we may be beginning to see the ways in which genetics plays a significant role in how different people will benefit from metformin use.

Second, the effect on dementia is yet another clue that the biological programs impacted by metformin may exist significantly upstream of the conditions it impacts. Indeed, metformin might not work on diabetes and dementia, or even both – it might work on aging itself, which is the single biggest risk factor for both of these diseases. If that is the case, it is not unlikely that future studies will continue to demonstrate an effect on other age-aggravated diseases.

This, of course, aligns to hypotheses that have been rather famously proffered by Nir Barzilai, whose Targeting Aging with Metformin (TAME) trials may have a tremendous impact on the prescribing paradigm.

With more and more positive data accumulating, will metformin be used more widely to prevent age-related diseases? Will it be the first drug to be prescribed specifically for the condition of aging?

Barzilai believes that day is coming. He has predicted that if the technologies available now are used widely, and those like cellular reprogramming and senescent cell deletion come to fruition, the traditional Hebrew blessing “Ad me’ah ve-essrim shana,” or “May you live until 120,” may need updating, for it will be a wish not for a long life but for an average one.

Imagine that.

.png)

Comments

Post a Comment